Back again! This time I want to continue with some offensive material (ha!, not that kind of offensive).

It’s been a while since I’ve posted this type of content and instead of the usual HTB walkthrough, I figured I’d switch things up a bit. As much as I enjoy working through AD environments, I’ve always had a soft spot for web security; I’ll admit, I’m a little biased here. Some of the best web training material out there lives on PortSwigger’s Academy and it’s hard not to appreciate how well structured their material is.

For this post, I’ll walk through a very simple module that demonstrates basic SQL techniques used to bypass login controls. Because the exercise itself is short and straightforward, I’ll use it as an opportunity to go a bit deeper into the technical side and expand on SQL injection concepts more broadly.

Let’s get into it.

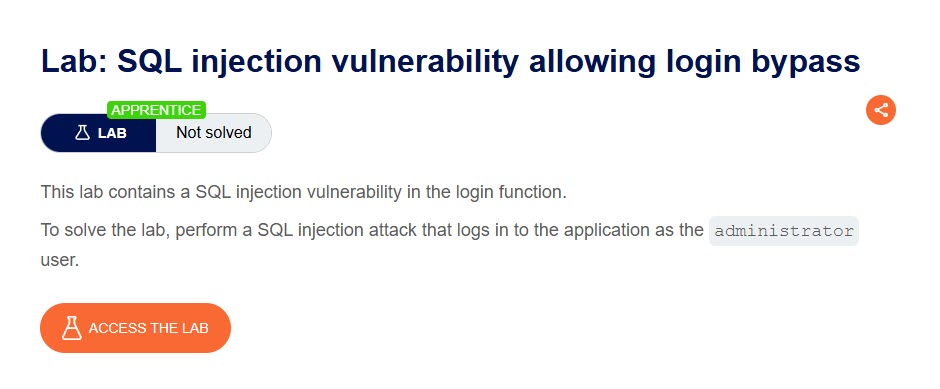

This lab titled SQL injection vulnerability allowing login bypass explores a SQL injection attack that allows the attacker to log into the application as the administrator.

The description here is crucial, as it provides key details about how we should approach exploiting the application. We’re told the account we’re targeting is named administrator, and even without any hint about the password, we already have more than enough to work with.

Now before jumping into exploitation, it helps to understand how SQL actually works, and more importantly, how we can manipulate the logic behind it.

SQL Logic Crash Course

When you submit credentials into a login form, that data doesn’t magically validate itself. The application typically takes your input and builds a SQL query that is sent to a backend database. That query might look something like:

SELECT * FROM usersWHERE username = 'admin'AND password = 'password123';

If the query returns a valid row, access is granted. If not, access is denied.

The problem arises when user input is directly inserted into the query without proper validation or parameterization. If the application blindly concatenates user input into the SQL statement, we can alter the structure of the query itself not just the values.

To understand how this breaks, we need to understand a few important SQL concepts:

String Delimiters (‘)

Most login queries wrap user input in single quotes. If we inject our own quote, we can prematurely terminate the intended string and begin writing our own SQL logic. For example:

admin'

Now the query structure changes because we’ve closed the original string.

Boolean Logic (OR, AND)

SQL evaluates conditions logically. If a WHERE clause evaluates to TRUE, the query returns results. If we inject something like:

' OR 1=1 --

The resulting query becomes:

SELECT * FROM users

WHERE username = '' OR 1=1 --'

AND password = '';

Since 1=1 is always true, the condition succeeds regardless of the password. We’ve effectively bypassed authentication.

Comments (--)

SQL uses -- to indicate a comment. Everything after it on that line is ignored.

This is powerful because once we inject our own logic, we can comment out the rest of the original query, such as the password check, preventing syntax errors and removing unwanted conditions. For example:

' OR 1=1 --

The -- ensures that anything following it is discarded by the SQL engine.

Side Note: In many SQL dialects, -- comments require a trailing space/newline (-- ). PortSwigger labs usually accept it either way, but in real apps it matters.

The Core Issue: Query Construction

The root cause of SQL injection isn’t “special characters”, it’s improper query construction. When developers build SQL statements by concatenating strings instead of using parameterized queries (prepared statements), they allow user input to alter the intended structure of the query.

That’s the real vulnerability: the application trusts user input as part of executable SQL.

In this lab, we don’t need complex payloads or advanced enumeration techniques. We simply need to understand how the login query is likely structured and then modify its logic so that the database returns a valid result, even without knowing the administrator’s password.

Now with this information in mind, let’s move on to the lab and take a dive into how we can bypass the login page.

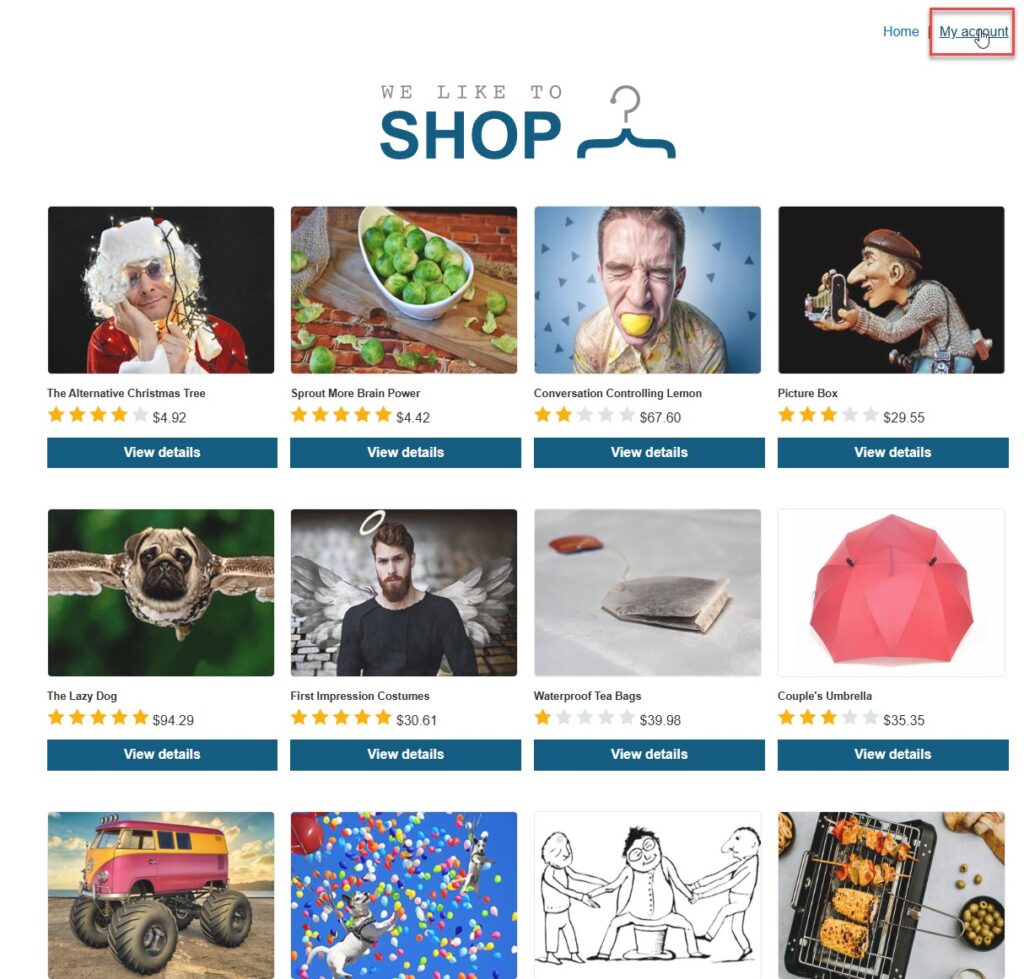

With the lab loaded up, we can navigate to the login page located under “My account” on the upper right-hand corner.

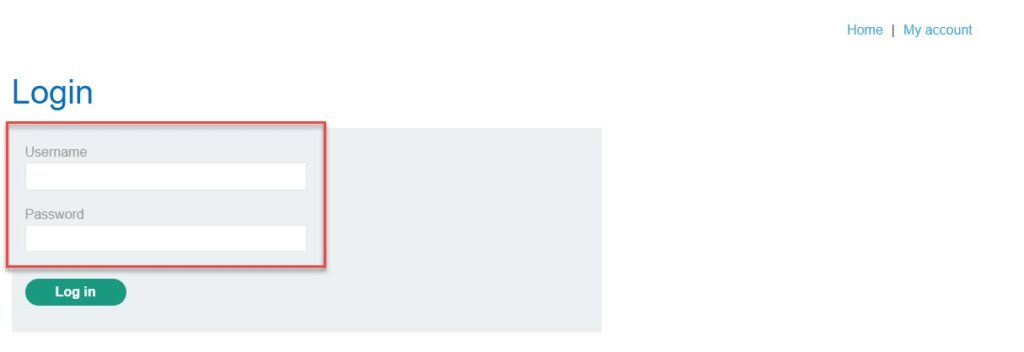

From here, we’re presented with a fairly generic login page. At first glance, it invites the usual approach: try common credentials like admin/password, administrator/admin123, or other predictable combinations. That kind of testing can be useful in real assessments, especially when default credentials are in play.

But brute forcing isn’t the goal here.

We’re not trying to guess the password. We’re trying to eliminate the need for one entirely.

If the application is vulnerable to SQL injection, the authentication check itself becomes the target, not the credentials. Instead of asking, “What is the administrator’s password?” we should be asking, “How is the application verifying it?”

Once we understand that the login form likely builds a SQL query behind the scenes, the objective shifts. Rather than supplying valid credentials, we aim to manipulate the query so that the database returns a successful result regardless of the password provided.

In other words, we’re not attacking the account, we’re attacking the logic that protects it.

At this point, we want to observe how the application behaves when it receives unexpected input. Even though the lab title tells us SQL injection is in play, that luxury doesn’t exist in real-world testing. In an actual engagement, there are no spoilers, you have to infer vulnerability from behavior.

A simple and effective starting point is to input a single quote (') into one of the login fields.

Most SQL queries wrap user-supplied input in single quotes. If the backend query looks something like:

SELECT * FROM users

WHERE username = 'username'

AND password = 'password';

Then injecting a single ' can prematurely terminate the intended string. If the application is not properly handling or sanitizing input, this will often cause a SQL syntax error. For example, entering:

'

May transform the query into something syntactically invalid:

SELECT * FROM users

WHERE username = '''

AND password = '';

If the application responds with:

- A database error message

- A stack trace

- A different response than usual

- Or even just a subtle behavioral change

That’s a strong indicator that our input is being directly embedded into a SQL query without proper protection.

Even if we don’t see a verbose error message, differences in response time or output can still signal that we’re interacting with the database layer in a meaningful way.

This step isn’t about exploitation yet, it’s about confirming that the input affects the underlying query structure.

Once we confirm that, we move from “testing input” to “manipulating logic.”

Let’s try this approach by entering a single quote and see where it takes us.

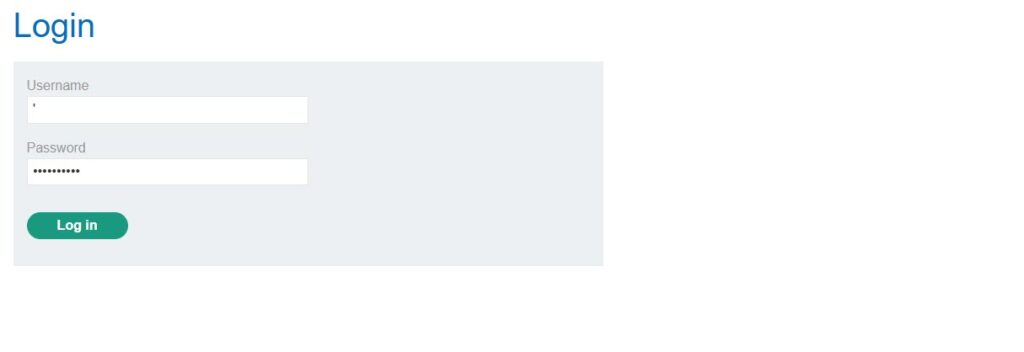

This results in an internal server error.

Bingo!

That response tells us something extremely important: our input is influencing the backend query structure. The application didn’t simply reject the input as invalid, it attempted to process it and failed at the database layer.

An internal server error in this context strongly suggests that the single quote disrupted the SQL syntax. In other words, the application likely constructed a query using our input directly, and the database engine threw an error when the query became malformed.

That’s the confirmation we were looking for.

At this stage, we haven’t bypassed authentication yet, but we’ve proven that the login form is vulnerable to injection. The input is not being properly sanitized or parameterized, and we now know that we can alter the logic of the query itself.

From here, the goal shifts from detection to exploitation, let’s move on.

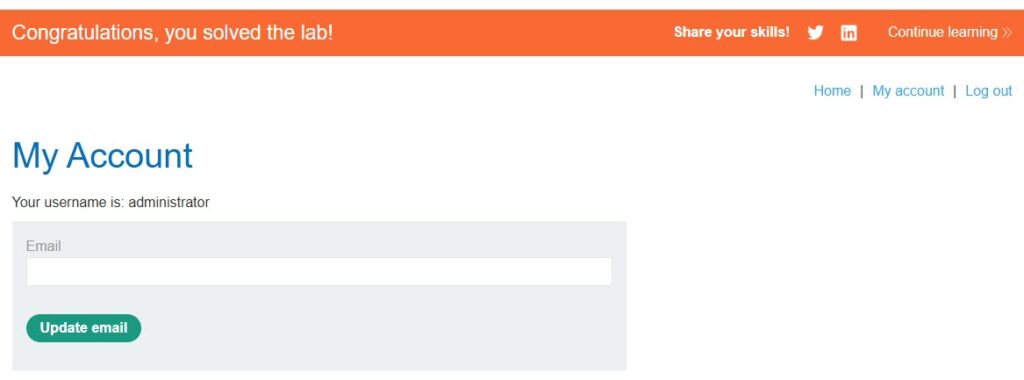

With that confirmation in hand, the rest of the lab becomes fairly straightforward. We’ve established that the login form is vulnerable to SQL injection, and we already know the target username: administrator.

Now we can move from detection to bypass.

A simple payload to test is:

administrator'--

What this does is close the original string in the query and then use the SQL comment operator (--) to ignore everything that follows (i.e. the password check).

If the backend query originally looked something like:

SELECT * FROM users

WHERE username = 'administrator'

AND password = 'password';

Our injected payload transforms it into:

SELECT * FROM users

WHERE username = 'administrator'--'

AND password = 'password';

Because -- comments out the remainder of the line, the AND password = 'password' portion is never evaluated. The database only checks whether the username exists.

If the administrator account is present in the database, the query returns a valid row and authentication succeeds without ever verifying a password.

Notice what happened here: we didn’t guess anything. We didn’t brute force anything. We simply altered the structure of the query so that the password comparison was removed from execution entirely.

This is the essence of SQL injection in authentication contexts, not breaking the password, but breaking the logic that enforces it.

Conclusion

This lab may have been simple, but it highlights a fundamental truth about SQL injection: we’re not attacking passwords, we’re attacking logic.

By injecting a single quote and observing the application’s response, we confirmed that user input was being embedded directly into a SQL query. From there, bypassing authentication wasn’t about guessing credentials. It was about altering how the database interpreted the query itself.

A payload as simple as administrator'-- worked because the application trusted raw input and constructed its SQL statement through string concatenation. The database did exactly what it was told and that was the problem.

In real-world scenarios, vulnerabilities like this are rarely labeled for you. There are no hints, no lab titles, and often no verbose error messages. The methodology, however, remains the same:

- Probe for abnormal behavior.

- Confirm input affects query structure.

- Manipulate logic, not data.

The fix for issues like this is well known: parameterized queries, prepared statements, and proper input handling eliminate the ability for user input to alter query structure. SQL injection is not a new vulnerability, but it persists nonetheless. When the boundary between data and logic isn’t strictly enforced, the database will execute whatever it’s given, correctly and obediently.